What problem does DNS solve?

Computers communicate using numerical addresses. Humans do not.

Every system connected to an IP network needs an address so other systems know where to send traffic. These addresses are efficient for routing packets, but they are difficult for people to remember and change frequently as infrastructure evolves. Early networks worked around this by sharing static name lists, but that approach quickly broke down as networks grew larger and more distributed.

The Domain Name System, or DNS, exists to separate naming from addressing. It allows people and applications to rely on stable, human-readable names such as example.com, while the underlying network destinations can change over time. Servers can move, scale, or fail without requiring users to track those changes.

At its core, DNS answers a simple but critical question: When a system asks for this name, what network information should it use right now?

What DNS is, and what it is not

DNS is a naming system. It is not the internet itself.

DNS does not carry application data. It does not transmit web pages, deliver email, or establish network connections. Its role is limited to providing information about names so that other protocols know where to connect. Once a name is resolved, DNS is no longer involved in the communication.

A useful mental model is a directory rather than a conversation. DNS tells a system where to go. What happens next depends on transport and application protocols such as TCP, UDP, HTTP, or SMTP.

Because DNS is consulted early in most network interactions, failures tend to be highly visible. When name resolution fails, applications often appear unreachable even though the underlying network may still be functioning correctly.

DNS and the network stack

DNS is often described as “a protocol,” which can be misleading without context. In teaching models like OSI, DNS is usually placed at the application layer because it defines message formats and behavior between systems. In practice, DNS exists to support other applications rather than deliver application data itself, and its queries are carried over transport protocols such as UDP or TCP. This is why DNS often appears to sit between layers and why DNS issues can surface as application failures even when the network is otherwise functioning normally.

DNS as a distributed, hierarchical system

One of the most important design choices in DNS is that it is distributed.

There is no single database that contains every name on the internet. Instead, DNS divides responsibility across a hierarchy, with each layer knowing only how to direct queries to the next layer. This limits how much information any one system must maintain and avoids a single point of control.

At the top of the hierarchy are the root servers. They do not store records for individual domains. Their job is to point resolvers toward the correct top-level domain servers, such as those responsible for .com or .org.

Top-level domain servers, in turn, know which authoritative servers are responsible for a specific domain, such as example.com. Only the authoritative servers for that domain hold the actual DNS records that answer questions about it.

This delegation model allows DNS to scale globally while remaining resilient to failure and administrative change.

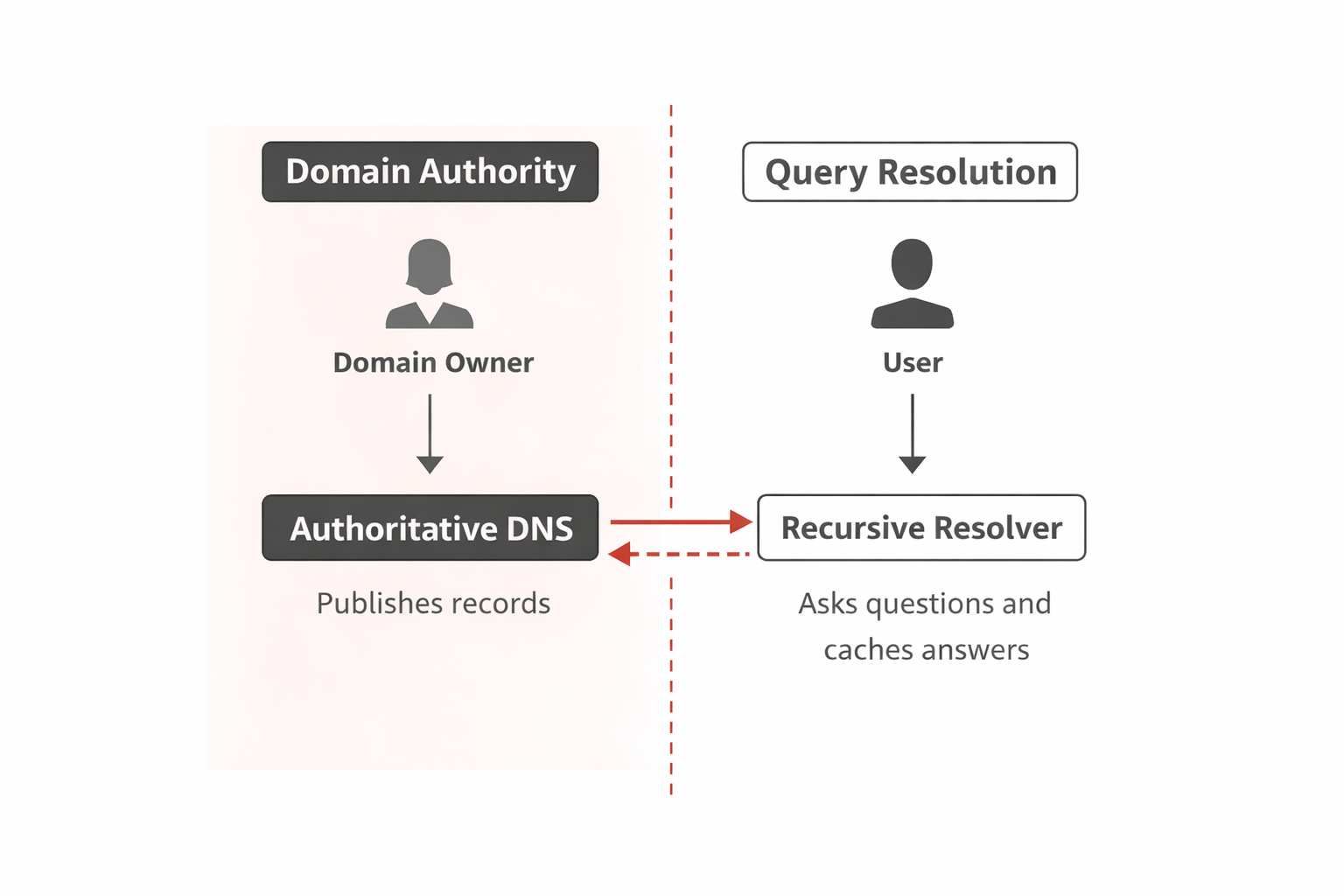

Separation of authority and resolution

DNS works because responsibility is divided between distinct roles.

Authoritative servers are controlled by domain owners. They publish DNS records and define what information exists for a domain. They do not perform recursive lookups or answer questions for unrelated domains.

Resolvers, often called recursive resolvers, answer questions on behalf of users and applications. They follow the DNS hierarchy, query authoritative servers as needed, and cache responses so the same work does not need to be repeated for every lookup.

These roles are intentionally separate. Resolvers do not own the data they retrieve, and authoritative servers do not need to understand the full DNS namespace.

This separation avoids centralized control and allows independent organizations to operate DNS infrastructure cooperatively.

Why DNS Is Designed This Way

DNS was designed in the early 1980s, when networks were smaller, slower, and far less reliable than they are today.

Bandwidth constraints favored compact responses. Network latency made caching essential. Central coordination became a bottleneck as networks grew. These realities shaped DNS into a system that favors delegation, reuse of information, and eventual consistency rather than immediate global synchronization.

While modern networks look very different, DNS retains this structure because it continues to scale reliably under global load.

What this means in practice

In real networks, DNS resolution involves cooperation between multiple independent systems. Each contributes partial information and relies heavily on cached results to reduce load and latency.

This also means that changes to DNS data do not propagate instantly everywhere. That behavior is intentional. DNS trades immediate consistency for scalability and fault tolerance.

Understanding DNS as a distributed system helps explain why behavior can vary across networks even when authoritative data is correct.

Summary

DNS maps human-readable names to machine-usable network information.

It is:

- Distributed rather than centralized

- Hierarchical, with delegated responsibility

- Focused on naming and direction, not data transfer

It is not:

- The internet itself

- A transport or security protocol

- A guarantee of availability or trust

DNS behaves the way it does because it was designed to scale, tolerate failure, and allow independent control across a global network. Those design choices form the foundation for everything that follows in the DNS Library, including why DNS is frequently targeted by attackers.